Two English researchers unravel the state of the country’s health system at an event at UFRJ. The subversion fueled by neoliberal policies empowers the private sector – while people suffer from the erosion of care.

The National Health System (NHS), the public and universal health system in the United Kingdom that inspired the creation of the SUS, may be at a breaking point. This is what Kate Bayliss of the University of Sussex and Soss and University of London and Jasmine Gideon of Birkbeck University warn. They attended a seminar organized by the Institute of Economics of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (IE-UFRJ), with the support of Abrasco and Fiocruz. Lina Lavinas, full professor of IE-UFRJ, was the moderator and Francisco Funcia from ABrES gave the presentation. The two researchers described how the private sector is advancing in British health care, particularly after “austerity” policies. And people are suffering…

Strikes and protests in recent months organized by NHS professionals such as junior nurses and doctors are a visible tip of the crisis in the British health system. But for people living in one of the world’s richest countries, the truth is clear: The system doesn’t guarantee universal care. In her presentation, Jasmin painted a portrait of some of the worst indicators of British health. Workers, especially nurses, suffer from lower wages today than they did ten years ago. They have to resort to basic government schemes. They fight for better conditions, but get in return a vague plan that doesn’t address the decline in their wages.

After the pandemic, as in many parts of the world, the situation worsened. Today, the waiting list for elective surgeries attracts 7.47 million Britons – seven times more than Brazil, with a population three times smaller. There is a shortage of 110,000 professionals. Maternal mortality increased by 3%. Lack of tooth protection leads to ridiculous situations such as resorting to at-home, “do-it-yourself” tooth extractions with pliers. And there are clear disparities that affect immigrant populations in particular. They are not guaranteed the right to an interpreter in their language, they are charged for procedures, and they are mistreated by doctors. How did it get to this point?

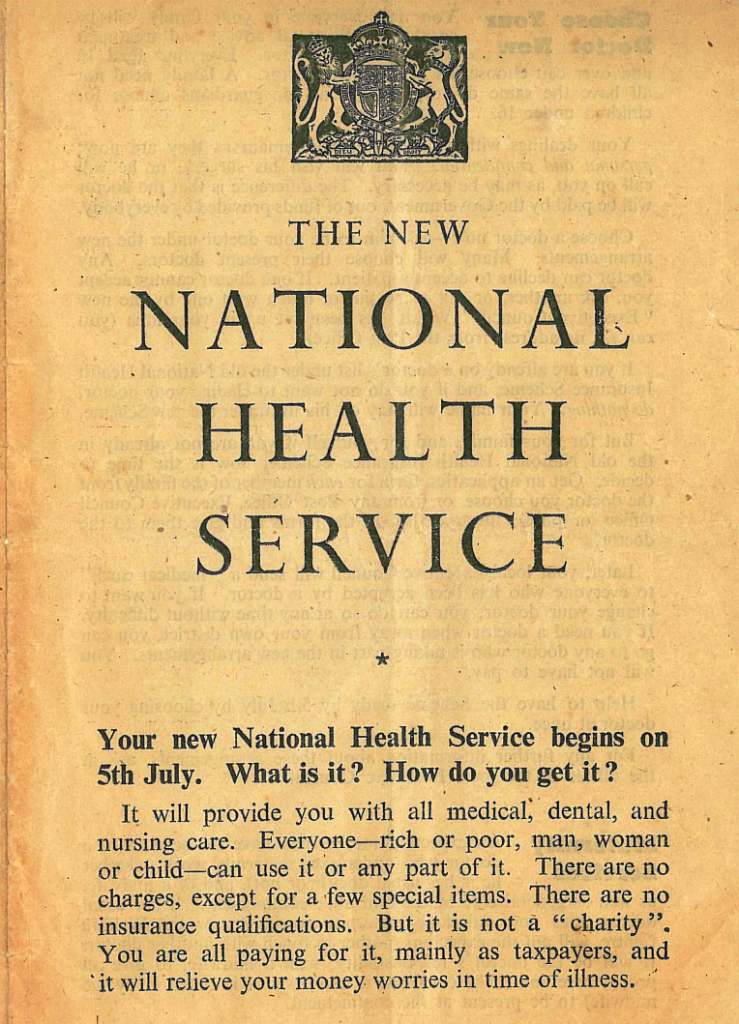

In her speech, Kate traces the 75-year history of the NHS to answer this question. At the time of his inauguration, he retrieved a poster announcing the “New National Health System” and asserted: “Poor or rich, men, women or children – everyone can use it. […] It is not about ‘charity’. Everyone pays with their taxes, and the system eases financial worries during times of illness. But that plan is deteriorating.

The process in the NHS is similar to what happens in the SUS. One of the main gateways to private healthcare in the public system is the hiring of specialists by private companies – making the jobs of doctors, nurses and other staff precarious. But there are differences: in the UK, few have health plans. What often happens is that citizens pay out of pocket for care or procedures. Today, 83% of health care spending in the country is public, while 13% is private — one percentage point higher than the average for high-income countries, says Kate. There are some sectors that are heavily involved in private healthcare, such as routine surgeries: 30% of which are performed outside the NHS.

Kate highlights three areas where organizations are increasingly gaining control. Dental care: The NHS only guarantees dental care for children and pregnant women. Mental Health: Services are provided by the private sector but funded by the government. And so-called “community health”, similar to SUS’s primary care. The researcher also observes a larger trend of NHS partnerships, particularly with North American healthcare institutions.

“They say the NHS is being privatised. But that’s not really happening when it comes to privatizing the public. The system is being eroded in very subtle and harmful ways,” Kate summarizes. And it comes from decades of “austerity” policies which, he says, have helped open the doors for companies to enter the NHS.

But the failure of the neoliberal healthcare model is also expressed in the inability of the private sector to develop more aggressively. “Austerity”, the uncertainty of the workforce and the financial deterioration of the British means that most people cannot afford to pay for healthcare when they cannot find services on the NHS. This leads to a decline in health indicators, and is another example of the continent’s decline in social welfare policy.

“Total creator. Devoted tv fanatic. Communicator. Evil pop culture buff. Social media advocate.”