The strength of solar storms hitting Earth can vary greatly over very short distances, with locations just a few tens of kilometers away experiencing very different magnetic perturbations, according to a new study by the Sodankyla Geophysical Observatory (SGO) in Finland.

According to the researchers, this may mean that some regions are more vulnerable to large solar storms than previously thought. Currently, most solar storm monitoring networks have sensors spaced 400 km apart on average. However, the study found that the intensity of solar storms varies over much smaller distances, about 100 km.

Observe the past

(Source: Getty Images)

(Source: Getty Images)

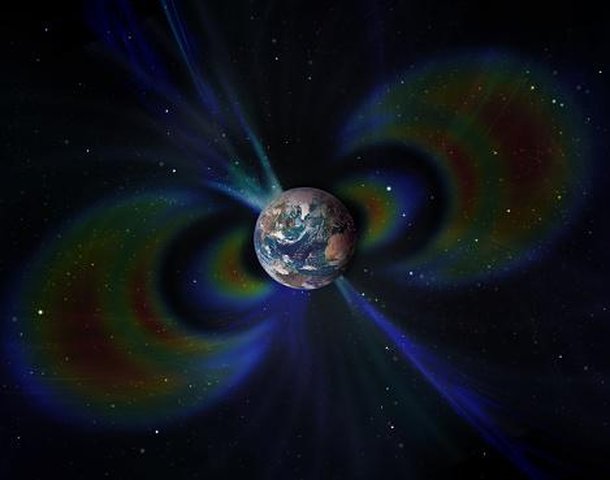

In the view of study author and SGO Director Eija Tanskanen, when a solar storm occurs, a network of widely spaced magnetometers can lead to an underestimation of local magnetic disturbances. These storms occur when powerful blasts of charged particles from the Sun hit the Earth’s atmosphere.

The atmosphere protects the planet’s surface from most of these charged particles, although satellites in low orbit are at risk from electrical storms and damage. When storms are large enough, they can cause aurora borealis to occur at lower latitudes than usual. In the worst cases, solar storms can disrupt electrical grids.

To study the basic details of these effects, researchers from SGO and the University of Oulu in Finland monitored a case dating back to 1977. That year, a powerful solar storm hit the world and was recorded by 32 stations on the Scandinavian Magnetometer Array (SMA). This collection of magnetic field sensors was denser than the monitoring networks currently operating in the Nordic countries, but was never digitized – making data analysis difficult.

Human unpreparedness

(Source: Getty Images)

(Source: Getty Images)

For the new study, the researchers photographed and digitized records from 1977, and found that the variations from season to season were extreme. In a powerful solar storm, such as the Carrington Event of 1859 — which cut off telegraph communications — up to a 150 nanotesla difference in magnetic disturbance can occur over 10 kilometers away.

This means that one area could go unnoticed by the data, while a location a short distance away could be exposed to hundreds of times the intensity of solar storms. The discovery of these numbers serves as an argument for humans to note the need to add more sensors to the network that measure changes in the Earth’s magnetic field.

According to Tanskanen, a denser network of magnetometers would help us understand the complex structure of the magnetic field during solar storms. With the addition of new monitoring systems, we can provide local alerts on the movements of solar storms and improve protection of infrastructure vulnerable to magnetic disturbances. Meanwhile, humanity remains unprepared.