“Take back control.” The slogan of the Brexit campaign, the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union, was a call to take back control of immigration policy, ending the ability for EU citizens to live, work and study freely in the United Kingdom.

But in the years since Brexit, the country has seen some of its fastest population growth since the 1960s, making immigration one of the key themes of the UK’s upcoming general election, due to be held on July 4.

But after all, what happened?

To understand the issue of immigration in the UK, a good starting point is the English coastal town of Skegness. There, more than three-quarters of the population voted to leave the European Union.

As in many parts of the UK, when it comes to immigration, much of the focus is on those who arrive in the country illegally.

“Stop the boats” is a key promise of the ruling Conservative Party, a reference to the tens of thousands of people who make the dangerous crossing of the English Channel, often in rubber dinghies of questionable quality.

Although none of these boats have reached Skegness, it is an issue that concerns the town. Until recently, several coastal hotels were used to house asylum seekers while their applications were being processed.

It’s causing problems in the community, says Julianne Ponce, who runs the North Parade Hotel.

“They didn’t cause us any trouble,” she says.

“(But) the general feeling in the Skegness area is that people don’t want them here.”

The vast majority of asylum seekers have already been removed from hotels, but local concerns about the impact of migration remain.

The vast majority of them immigrate legally.

So, you can imagine that the record increase in migration has been driven mainly by people arriving in the UK illegally.

In 2022, the migration balance – the difference between the number of people arriving in the UK and leaving it each year – is estimated to hit a historic record of 745,000.

In 2023, the number is believed to have reached 672,000. In the same year, 30,000 people arrived in small boats.

The vast majority of those who arrive in the UK do so legally. These are people like Kiki Ekweg, who works in a supported living complex in Skegness.

While she was making her rounds, she knocked on the door. “Hello! It’s cheeky (Something like ‘naughty’) Kiki!” she says, laughing as she enters.

“Being a caregiver is not an easy job,” she says. “You need to have mental balance, you need compassion, and you need a lot of patience.”

Kiki emigrated from Nigeria to the UK, initially to study at university, but stayed there to work.

Students and health and care professionals like Kiki made up around two-thirds of the visas granted by the UK last year, and are the main driver of the rise in net migration since the 2000s, according to the Oxford University Migration Observatory.

So the numbers of arrivals, which former Prime Minister Boris Johnson described as “scandalous” when they were at a much lower level than they are today, are in fact, to a large extent, the result of deliberate policy decisions by the government.

So what happens?

The truth is that successive governments have realised that the UK needs migrants.

International students pay much higher tuition fees, which essentially subsidises domestic students. If the number of international students falls, UK students may have to pay more; universities may go bankrupt; or the government may need to fund them. None of this will be popular.

Moreover, many sectors of the UK economy, particularly health and social care, are experiencing severe worker shortages.

One in five of the 1.5 million people working in the NHS, the UK’s public health service, are foreign nationals.

But despite the increase in immigration, there were still 150,000 jobs open in the health care sector last year.

The impact of Brexit

While it is surprising that Brexit coincided with an increase in immigration, Brexit did result in a reduction in the number of one group.

In the 12 months to June 2023, the bloc’s migration stock was -86,000, meaning more EU citizens left the UK than came into it.

But they were replaced by people from the rest of the world. About 250,000 people arrived from India, and just under 150,000 from Nigeria. China, Pakistan and Zimbabwe are the next most common places of origin.

“Stop the boats”

However, it is illegal immigrants who have dominated political discourse in the UK.

In the midst of the election season, “Stop the Boats” has become a recurring campaign slogan.

Current Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has made it one of his five priorities.

To solve this problem, he devised a plan to send some asylum seekers who had arrived illegally to Rwanda.

But the opposition Labour Party has promised to abandon the plan and instead plans to create a new Borders and Security Command to help remove ineligible asylum seekers.

The newly formed Reform Party in the UK (the far-right party) has promised a zero-tolerance approach, including withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights.

Does the UK take in more migrants than other countries?

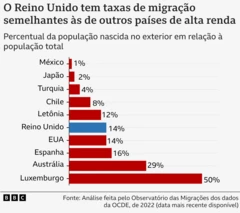

The UK is generally in line with other high-income countries when it comes to immigration.

In 2022, 14% of people living in the UK were classified as “foreign-born” – a similar proportion of the population to countries such as the US and the Netherlands.

But when we look at countries like Canada, New Zealand and Australia, we see a different scenario emerging. In Australia, for example, the foreign-born population is twice as large as in the UK as a percentage of the population.

hard compromises

So we return to our original question: why is net migration in the UK so high, eight years after leaving the EU?

The truth is that immigration was not just driven by freedom of movement. The UK economy needed immigration, despite the political rhetoric.

Many of the decisions needed to significantly reduce the number of people arriving in the UK will require difficult trade-offs, which the government has been reluctant to make.

Illegal immigration, especially through dangerous routes, is something that all sides are quick to oppose – and it ends up being the focus of the debate.

Back in Skegness, Kiki knows about it.

“I watch the news so I don’t completely ignore what’s happening,” she says when asked about the immigration debate, as she walks past the city’s coastal attractions.

“If people have negative impressions, it has been misinterpreted, in my opinion. I don’t think they really understand what is happening on the ground. I think they have been misunderstood.”