Enceladus doesn’t look like much. They are monochromatic and small, and pale in comparison to Saturn’s large, showy rings.

But as many objects in the solar system demonstrate, appearances can be very deceiving. Enceladus has a lot more going for it than an initial glimpse might indicate. A new analysis suggests that the icy world is home to many more organic molecules than previous findings indicate.

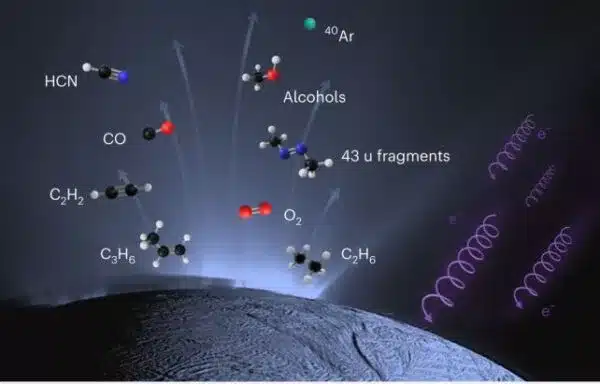

A closer look at data from Saturn’s Cassini probe revealed that Enceladus is spewing molecules like methane, ethane and molecular oxygen from geysers spewing liquid water deep within its icy atmosphere.

It’s a discovery that also builds on the idea that the moon could support some kind of biochemistry, or even communities of microbes, in its global surroundings, adding support to calls for a dedicated mission to Enceladus in the hopes of finally finding extraterrestrial life.

“The results presented here suggest that Enceladus hosts a compositionally diverse, multi-stage chemical environment consistent with a habitable subsurface ocean,” wrote a team led by astrobiologist Jonah Peter of Harvard University and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“Species [químicas] “What was identified in this work also suggests that this ocean may contain the building blocks necessary for the synthesis of compounds important for the origin of life.”

Previously unidentified organic molecules on Enceladus indicate a habitable environment. (Peter et al., Nat Astron, 2023)

Most of what we know about Enceladus comes from the Cassini mission, which explored Saturn and its moons from 2004 to 2017. We didn’t know much about the small, icy moon before then; But then the probe detected clouds of fog rising from cracks in Enceladus’ icy surface, revealing a churning liquid ocean below.

Subsequent analysis of data collected by Cassini and the Intraneutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) revealed the presence of organic molecules in these plumes – water, carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia and molecular hydrogen.

But INMS has low mass accuracy, which makes it difficult to identify less abundant species, as there is a fairly wide range of possible groups that can fit the data. Therefore, the complete profile of the columns remains an open question.

Peter and his colleagues, planetary scientist Tom Nordheim and astrobiologist Kevin Hand of JPL, took another look at the IMNS data. They used statistical modeling to compare the data with a large library of known mass spectra to determine what could produce the patterns seen in the Cassini data.

Their results confirmed previous findings while revealing a wider range of organic molecules than initially identified, including hydrogen cyanide, acetylene and propylene. Compounds involved in prebiotic chemistry – the chemistry that leads to the formation of life.

We have some convincing evidence that Enceladus has an active hydrothermal environment. It orbits around Saturn, causing the moon to expand and compress, heating its interior. This thermal energy can seep through openings on the ocean floor, providing a favorable environment for life, even far from the sun. We know this because it occurs deep in Earth’s oceans.

We cannot know at this stage whether what we have discovered so far means there is life on the surface of Enceladus. It could just be a bunch of molecules, hanging out by chance. But the interesting thing is that it can be really important. We can conduct laboratory experiments here on Earth to try to determine whether or not Enceladus is inhabited, but really, the only way to know for sure is to explore further.

There are currently some proposed missions for Enceladus, but nothing has been decided yet. However, every drop of evidence brings us one step closer to visiting that alien moon and searching for those strange bacteria.

“Our results suggest the existence of a chemically rich and diverse environment that could support complex organic structures and perhaps even the origin of life,” the researchers wrote.

Translated by Matthews Lineker from Science Alert